Art has had an uneasy relationship with commerce for centuries. As artist and Working Artists and the Greater Community (W.A.G.E.) core organizer Lise Soskolne said in a recent panel discussion called “Art Works?” artists function both inside and outside the market living in a weird, nebulous realm that simultaneously infiltrates each and every class of society from the poorest of the poor to the 1% of the 1% while also examining, critiquing and contradicting those very same societal rungs and structures on which they depend to pay the bills.

Even what artist means has shifted over time, predominantly due to the market in which art exists. Earlier this year, William Deresiewicz charted in The Atlantic in an essay called “The Death of the Artist – and the Birth of the Creative Entrepreneur” the evolution of our cultural understanding of artist from hard-working artisan to solitary genius to credentialed professional to today’s creative entrepreneur, a transition he laments. “When works of art become commodities and nothing else, when every endeavor becomes ‘creative’ and everybody ‘a creative,’ then art sinks back to craft and artists back to artisans – a word that, in its adjectival form at least, is newly popular again. Artisanal pickles, artisanal poems: what’s the difference, after all?”

But to our minds Deresiewicz, at least, appears to be caught inside a Portlandia episode. Art functions as a commodity, that’s true, but it also goes beyond economics. Art is not merely a product, something to be bought and sold. It’s at once tangible and intangible. For the businesses we work with, art provides multiple values: activating and humanizing spaces, creating unforgettable environments, attracting and retaining talent and customers. How can you put a monetary value on those things?

Perhaps these unquantifiable benefits are why “Artists,” Soskolne says, “are [believed to be] compensated in ways that transcend commerce such as the intangible rewards of the so-called creative process: love, satisfaction, self-expression and so on.” Art for art’s sake is payment enough, or so the theory goes, reinforcing the romanticized and fetishized myth of the starving artist. But as even Van Gogh (the epitome of the starving artist) knew, an artist’s got to eat and more than just Patti Smith’s lettuce soup, if she wants to sustain her art practice over the course of a career.

Research and data has accumulated over the years to try to quantify how artists make a living. But like trying to define art, this proves tricky if mind-breaking/treacherous/ridiculous exercise. The National Endowment for Arts’ last study, released in 2011, counts 2.1 million artists in the United States with median wages and salaries of $43,000 (in 2009) – a number that exceeds the whole labor force by $4,000 yet lags behind other “professional” workers by $11,000. On the surface, these data points may seem promising, but once you unpack the numbers, they become less so. As Alexis Clements wrote for Hyperallergic, “Most reports about artists that I’ve seen (and I’ve seen a fair number) that are based on quantitative data are pretty fuzzy when it comes to the thing that many artists would love to know: How much money do artists make from their creative work?” She goes on to ask, “Why is the data so imprecise? Because almost everything about the ways that artists work seems to defy typical practices for collecting labor and earnings statistics…”

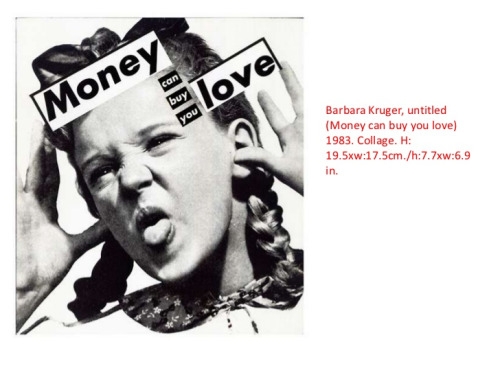

For example, this data accounts only for those whose primary profession is as an artist. In 2014, the NEA released a supplemental study called “Keeping My Day Job: Identifying U.S. Workers Who Have Dual Careers as Artists” citing an additional 271,000 workers who hold second jobs in artist occupations. Several Denver artists hold primary jobs in academia, museums, arts nonprofits, arts businesses and even non-arts related sectors: Derrick Velasquez teaches at Metro State University, Sandra Fettingis works at MCA Denver, Don Quade works at CenturyLink. Famous artists have often called directly upon their former day jobs for inspiration. Richard Serra once worked the West Coast steel mills and shipyards, Barbara Kruger once worked for magazines as a graphic designer, art director and photo editor, Andy Warhol worked in advertising. Still other artists like Tracy Weil and our own Xavian Lahey juggle multiple part-time gigs. Weil, in addition to his art sales, makes a living by helping communities build art districts in addition to selling heirloom tomatoes to local restaurants. Lahey works as Nine dot Arts’ part-time art handler and bartends to finance his BFA. In today’s economy, where many workers juggle several part-time gigs, studying even secondary jobs isn’t enough.

In her book The Artist’s Guide: How to Make a Living Doing What You Love, artist Jackie Battenfield advises artists to have multiple and varied income streams and says, “Precariously balancing yourself on one funding source…subjects your life and your art to the mercy of whatever happens to that resource.” Rather than confine yourself to day jobs and art sales alone, Battenfield advises artists to think of any and all other funding possibilities: grants, artist residencies, investments, awards, freelancing, consulting, bartering, in-kind donations, family, real estate. Local artist-founded and run studios like Ironton and TANK financially support the co-founders while also providing not only affordable studio space for other artists but also a collaborative working environment.

Back to the NEA data. For better or worse, the NEA counts commercial, industrial, fashion, graphic and floral designers and architects among artists as well as non-visual artists like musicians, actors, dancers, musicians and writers. Even the visual artists are lumped together with art directors and animators, which makes it impossible to see just how visual artists are faring. In their subset count totaling over 210,000 individuals, visual artists, art directors and animators, in 2009, earned a median wage or salary of almost $34,000 or $5,000 below the U.S. labor force as a whole and nearly $20,000 lower than other “professional” workers.

In an August 2015 article in The New York Times Magazine called, “The Creative Apocalypse That Wasn’t” author Steven Johnson makes the case that artists are faring slightly better, gross wages/salaries wise, in 2015 than in 1999, when pirated content from the internet threatened to undermine many artists’ livelihoods. He cites data that shows an increased number of creative workers as well as increased opportunities, lower overhead/capital investment required to create and the maker-to-consumer paradigm shift. Licensing, direct sales and Kickstarter campaigns mean more money for artists. The democratization of technology means increased access to tools and information. Gone is the gallery/agent/publisher middle man. But plenty of criticism has surfaced to counteract these claims.

Ken Tabachnick, a self-described “arts manager, educator, reformed intellectual property attorney and intermittently practicing artist,” agrees that the methods for making a living as an artist have changed over the last 20 years but counters that “Previously, artists had a realistic possibility to create valuable content and live off the exploitation of that content. Today, with the value of content being driven towards zero, it is rare to make a living solely from such exploitation and artists have had to evolve how they sustain themselves.” He goes on to state that “in most cases, artists have also had to pick up the work of building and maintaining a career that others…used to do.” Albuquerque-based artist Marietta Patricia Leis, who shows locally with Michael Warren Contemporary, recently told Nine dot Arts’ CEO, Martha Weidmann, about her shifting art practice. She formerly spent (and advised emerging artists to spend) 75% of her time making art and 25% working on the business side of her practice. Now, however, those percentages have flip-flopped.

Not only do artists have to contend with the mental, emotional and even physical demands of creating art, they must also deal with the often even more fraught demands of managing their financial outlook. Battenfield says artists “need to be better than the average person” at managing their money. And, because the art market and individual artist careers can fluctuate wildly from month to month, year to year, “You need to be comfortable managing your time and finances with a steady hand amid the ups and downs.” “Self-employed artists,” she says, “whether sole proprietors or incorporated entities, are responsible for maintaining accurate accounting records and filing the appropriate tax forms” and for providing their own “insurance: health, liability, disability and life. Work schedules, vacations, sick days and parental leave are self-determined.” Such control and responsibility can be both a blessing and a curse.

Examining gross wages and salaries can only tell part of the story of how and if artists make a living. As Tabachnick says, “a deep analysis” is needed to determine “whether artists are able to make a living on a net income basis and how today compares to the past.” Artists, for example, often face higher educational debt. The NEA found that artists of all types are, on average, more educated with 59% holding a Bachelor’s degree or higher. But, as several national publications have shown, Fine Arts degrees are among those with the “worst return on investment.” In a study by BFAMFAPhD titled “Artists Report Back: A National Study on the Lives of Arts Graduates and Working Artists,” 7 of the 10 most expensive schools in the nation (after scholarships and financial aid) are art schools. In today’s economy, a Bachelor’s degree, regardless of the industry, is seen as a baseline. For artists, the same often goes for an MFA. Clements calls this a “crazy hamster wheel at play” that forces artists to jump through hoops that are “really expensive and time consuming to jump through, which means only those who already have a lot of financial advantages and privileges in the first place are able to get through.” BFAMFAPhD showed in an earlier study that “The few people with art degrees who make their living as artists in New York City (15%) have median earnings of $25,000 a year. This is one-half of the median earnings of other professionals in the city, which is hard to face after going into debt for $120,000 for an art degree…” These kinds of hoops may directly contribute to the NEA’s findings of a decrease in demographic diversity among artists who tend to be pre-dominantly white and non-Hispanic.

In addition to debt, artists must contend with costs of living that can be highly disproportionate to their earnings depending on their resident city. With some of the least affordable cities in the nation also acting as cultural hub cities, affordable artist housing remains a top priority. In Denver, where apartment rental rates continue to skyrocket despite a glut of new buildings and where studio space is becoming increasingly scarce, many artists feel crunched from all sides. The River North Art District (RiNo), whose tag line many joke should be changed to “where art was formerly made,” has seen $365 million in real estate deals since 2013 which threatens to push those very same artists who made the area desirable out. Denver Arts & Venues and Artspace, a nonprofit arts development corporation, are working on plans to build a sustainable and permanent affordable artist community in RiNo in the near future. Artspace Loveland, developed by Artspace in conjunction with the City of Loveland, features 30 live/work lofts for artists. With rents based on income, a studio is as low as $323 a month – compared to the Denver metro area’s average monthly rental rates of $1,158 – for a single person whose average annual income is between $16,350 to $43,600.

Despite the data and surveys and statistics and anecdotes and theories that often purport otherwise, artists continue to make art and they continued to find ways to get paid to do so. Just as in creating art, there are no magic formulas to get paid for making art. Battenfield says “the same individuality you have established in your art practice will uncover a unique path to funding your art.” Money is not the enemy but rather “a tool,” as Battenfield describes it, which funds not simply supplies, studio space, food, shelter, health and well-being but also the means “to develop and realize new ideas…” Artists, as they’ve done throughout history, will continue to not only create but to work within whatever socioeconomic circumstances they find themselves. It’s not an easy task to make a living as an artist, but it can be done.

It’s our job – not just at Nine dot Arts but as the greater community as a whole – to make that struggle between creating art and paying the bills easier. Companies, especially, have the opportunity to make a positive impact upon the arts community through art purchases, artist fees for leasing work, scholarships, grants, stipends, fellowships, awards, in-kind donations like free studio space, travel vouchers and hotel rooms, pro bono services like legal advice, health screenings and tax preparation, or artist-in-residence programs. The possibilities are as endless and varied as art itself.