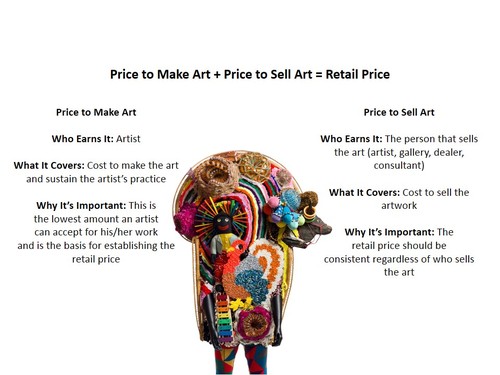

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2011. Mixed media. James Prinz Photography, Chicago. Courtesy of Nick Cave and the Jack Shainman Gallery, New York via Denver Art Museum.

With the close of the school year just around the corner, it’s BFA and MFA thesis time! Graduating artists, prepare yourselves for the inevitable: gifted copies (in triplicate or more) of Dr. Seuss’ Oh, The Places You’ll Go; questions from well-intentioned-yet-irritating family members about the future, specifically as it relates to your employment prospects (or lack thereof); and the end of the student loan grace period otherwise known as The Day You Decide to Sell Your Left Kidney/Future First Born on the Black Market. The onslaught of the real world and its bed-fellow association with that most dubious, stress-over, coveted, game-changer of a five-lettered word, money, are enough to make any graduate, artist or not, sweat.

It’s no secret that most of us have our issues with money – it’s easier for us to talk about what happens in the bedroom than it is to share how much the mattress cost. Pile the at-times secretive, seemingly loosey-goosey world of art pricing on top of that, and you’ve got a recipe for emotional and financial entanglement the size of the Hamilton Building. How are you supposed to price your art? Who decides how much it’s worth? What’s a fair price? Can’t you just opt out of the whole art market? Art for art’s sake, right?

Before we get into the down and dirty of art pricing, let’s take a brief philosophical detour. Many artists it seems have a guilt complex about earning money through creative endeavors, as if being paid for your art is the same as selling out. Let’s get a couple things straight. First, selling your art is a privilege. It means that someone else believes in your artistic vision and wants to support it financially. It also means that you believe in your work and yourself enough to turn your art practice into a verifiable career. Second, earning money through your creative output is an honorable (and enviable) way to make a living. Art remains incredibly important to the history of humanity, and you’re contributing to a conversation that dates back 15,000+ years. Plus, you’re taking the ballsy risk to not defer your dreams. Raisin in the sun be damned!” you shout. Not many people out there are willing to live so brazenly. And, let’s face it: an artist’s got to eat not to mention have a safe place to live, be healthy, save for the future, pay taxes and take care of all that other banal stuff that life constantly demands. Don’t think that selling out and selling your work are one and the same. Selling your work makes your life possible.

Tom Molloy, Swarm, 2006,

Mario Mauroner Contemporary Art, Vienna 2015

Courtesy Rubicon Gallery

Back to the issue at hand: pricing your work. As artist and teacher Jackie Battenfield says in her amazing book,The Artist’s Guide: How to Make a Living Doing What You Love, “The uniqueness of creative work and our emotional attachment to it make placing a value on our production difficult.” Note that she says difficult not impossible. You actually can make your prices “both logical and attractive” as Jackie says by following her steps:

- Ask yourself what it costs to make your art: material, overhead and time/labor costs plus a little extra for profit. At the very least, you should cover your costs to make the work.

- Consider factors that an appraiser would examine like rarity, permanence/cost of the materials and productivity. If the work is one of a kind, it’s more valuable than a 250-edition limited print. Likewise, a bronze sculpture will cost more than a paper sculpture not only because bronze costs more than paper but also because it has a staying power that paper does not. If your work is labor intensive, this may decrease your output. Because less of your work is available, it becomes more valuable, similar to unique pieces versus multiples. Generally, basic supply and demand applies.

- Compare prices among a wide variety of artists and galleries, locally, nationally and internationally, especially with work that is similar to yours or artists at a similar point in their careers. Even if the pricing is not readily available, ask about it. Be diligent and inquisitive until you’re familiar with the market and feel comfortable pricing your work. This helps you determine the fair market value of your artwork.

- Take an inventory of your work and price everything, even if it’s not for sale for insurance purposes. Do this when you have enough time and energy to devote to the task, not fifteen minutes before a meeting.

- Keep your price list handy! It’s easy to blank when someone asks for a specific piece’s price. Take a breath and say, “Let me double check.” Grab your list and refer to it. This way, your pricing will be consistent and not fall prey to whims, split-second decisions or naïve moments of under- or over-confidence.

- Once you’ve established a pattern of sales and/or you’re too busy to keep up with the current demand for your work, you can starting inching up your prices. If you’re harping over prices, think about how much better it is to sell four $1,000 pieces than it is to sell one $2,500 piece.

All of the above steps could be considered Part A of the pricing equation. Part B deals with retail and wholesale pricing, which probably have just as much emotional baggage as money itself. Wholesale doesn’t equate to cheap, discounted or commercial just as retail does not mean crazy-high mark ups and taking the consumer for all she’s worth. Rather, when you price your work, you should think of it in two parts: the wholesale price and the retail price.

Wholesale is the lowest price you can accept for a piece – it’s the price that covers the cost to make the art with a little something extra. Wholesale isn’t barely scraping by or undercutting yourself with a fire-sale price – it doesn’t break the bank. Rather, it’s the price that will comfortably sustain your art practice. Wholesale is important when you’re working with a gallery, dealer or art consultant because it’s the amount from the final sale that will go directly to you when a piece is sold. The wholesale amount is the guaranteed amount you’ll make from the sale regardless of who sells the piece.

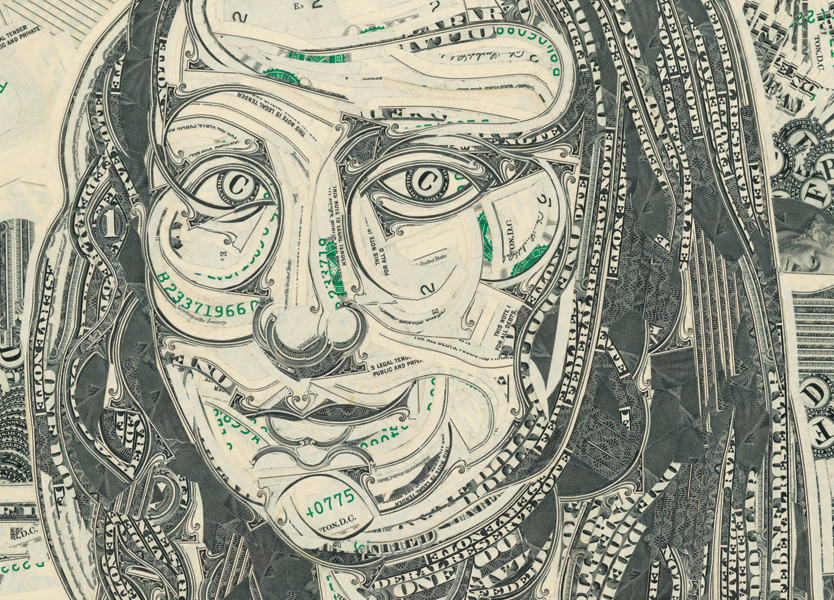

Money Lisa

Mark Wagner

Generally speaking, the retail price will be twice as much as the wholesale price. Think of the difference between the wholesale and retail prices as the cost to sell an art piece. Galleries, dealers and consultants, while they don’t create the art, spend an inordinate amount of time and resources selling art. A gallery, for example, pays rent, takes care of hanging and marketing an exhibit, cultivates collectors, works on your behalf with museums and deals with the press. If you use wholesale pricing for direct sales from your studio, you’re undermining the very people trying to help you succeed. If you sell a piece yourself, you should also reap the benefits of that time and effort. Keep in mind that you’re welcome to offer discounts for various reasons but make sure the buyer is aware of the retail price. Having just one retail price also makes your life easier in the long run because there’s just one number to keep track of. The retail price should remain consistent between sales from your studio, gallery, dealer or consultant.

To review, do your homework – on yourself and other artists. Know how much it costs you to make your art and know what other artists with similar work and career levels charge. Be organized. Keep a record of your pricing on hand and actually use it. Understand the difference between wholesale and retail and keep your pricing consistent across sales avenues. If you make a sale on your own, be sure to compensate yourself for that extra work. Having an art degree doesn’t preclude you from being smart about money. After all, two-thirds of smart is art.